In the course of a general talk I said that the first preoccupation must be to prevent further aggression in the future by Germany or Japan. To this end I contemplated an association of the United States, Great Britain, and Russia. If the United States wished to include China in an association with the other three, I was perfectly willing that this should be done; but, however great the importance of China, she was not comparable to the others. On these Powers would rest the real responsibility for peace. They together, with certain other Powers, should form a Supreme World Council. Subordinate to this World Council there should be three Regional Councils, one for Europe, one for the American Hemisphere, and one for the Pacific.

As for Europe, I thought that after the war it might consist of some twelve States or Confederations, Confederations, who would form the Regional European Council. It was important to re-create a strong France; for the prospect of having no strong country on the map between England and Russia was not attractive. Moreover, I said that I could not easily foresee the United States being able to keep large numbers of men indefinitely on guard in Europe. Great Britain could not do so either. No doubt it would be necessary for the United States to be associated in some way in the policing of Europe, in which Great Britain would obviously also have to take part. I also hoped that in South-Eastern Europe there might be several Confederations—a Danubian Federation based on Vienna and doing something to fill the gap caused by the disappearance of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Bavaria might join this group. Then there should be a Balkan Federation. I said that I would like to see Prussia divided from the rest of Germany, forty million Prussians being a manageable European unit. Many people wished to carry the process of division further and divide Prussia itself into component parts, but on this I reserved judgment. Poland and Czechoslovakia should stand together in friendly relations with Russia. This left the Scandinavian countries and Turkey, which last might or might not be willing, with Greece, to play some part in the Balkan system. Mr. Wallace asked about Belgium and Holland, suggesting that they might join France. I said that they might form a group of the Low Countries with Denmark. Mr. Wallace also asked whether I contemplated the possibility of Switzerland joining with France, but I said that Switzerland was a special case.

Each of the dozen or so of the European countries should appoint a representative to the European Regional Council, thus creating a form of United States of Europe. I thought Count Coudenhov Kalergi’s ideas on this subject had much to recommend them. Similarly, there might be a Regional Council for the Americas, of which Canada would naturally be a member and would represent the British Commonwealth. There should also be a Regional Council for the Pacific, in which I supposed that Russia would participate. When the pressure on her western frontiers had been relieved Russia would turn her attention to the Far East. These Regional Councils should be subordinate to the World Council. The members of the World Council should sit on the Regional Councils in which they were directly interested, and I hoped that in addition to being represented on the American Regional Council and the Pacific Regional Council the United States would also be represented on the European Regional Council. However this might be, the last word would remain with the Supreme World Council, since any issues that the Regional Councils were unable to settle would automatically be of interest to the World Council.

Mr. Wallace thought that the other countries would not agree that the World Council should consist of the four major Powers alone. I agreed, and said that to the four Powers should be added others by election in rotation from the Regional Councils. The central idea of the structure was that of a three-legged stool—the World Council resting on three Regional Councils. But I attached great importance to the regional principle. It was only the countries whose interests were directly affected by a dispute who could be expected to apply themselves with sufficient vigour to secure a settlement. If countries remote from a dispute were among those called upon in the first instance to achieve a settlement the result was likely to be merely vapid and academic discussion. Mr. Wallace asked what in practice would be the procedure if, for example, there were a dispute between Peru and Ecuador. I answered that it would be dealt with in the first place by the American Regional Council, but always under the general overriding authority of the World Council. In such an instance the interests of countries outside the American Hemisphere would hardly be affected; but plainly a dispute which threatened the peace of the world might very well not be susceptible to being treated only on a regional basis and the Supreme World Council would quickly be brought in.

I was asked whether the association of nations which I contemplated would be confined to the United Nations, or include the neutrals. I replied that there was advantage in trying to induce those nations at present neutral to join the United Nations before the end of the war, and that we ought to use all possible persuasion and pressure to secure this when it could be done with safety to the nation concerned. An example was Turkey. My policy was to help Turkey to build up her own forces to the point where, at the right moment, she could and would effectively intervene. When the United Nations brought the guilty nations to the bar of justice I could see little but an ineffective and inglorious rôle for Mr. de Valera and others who might remain neutral to the end.

We had much to learn, I said, from the experience of the League of Nations. It was wrong to say that the League had failed. It was rather the member States who had failed the League. Senator Connally agreed, and pointed to the achievements of the League in the years immediately after 1919. So did Mr. Stimson, who thought that if the original guarantee to France had not fallen through subsequent French policy, and also the history of the League, would have been very different. Force would clearly be required to see that peace was preserved.

I suggested an agreement between the United Nations about the minimum and maximum armed forces which each would maintain. The forces of each country might be divided into two contingents, the one to form the national forces of that country, and the other to form its contingent to an international police force at the disposal of the Regional Councils under the direction of the Supreme World Council. Thus, if one country out of twelve in Europe threatened the peace, eleven contingents would be ready to deal with that country if necessary. The personnel of the international contingent provided by each country would be bound, if it were so decided by the World Council, to undertake operations against any country other than their own.

Mr. Wallace said that bases would be required for these contingents. I said that there was something else in my mind which was complementary to the ideas I had just expressed. The proposals for a world security organisation did not exclude special friendships devoid of sinister purpose against others. Finally I said I could see small hope for the world unless the United States and the British Commonwealth worked together in fraternal association. I believed that this could take a form which would confer on each advantages without sacrifice. I should like the citizens of each, without losing their present nationality, to be able to come and settle and trade with freedom and equal rights in the territories of the other. There might be a common passport, or a special form of passport or visa. There might even be some common form of citizenship, under which citizens of the United States and of the British Commonwealth might enjoy voting privileges after residential qualification and be eligible for public office in the territories of the other, subject, of course, to the laws and institutions there prevailing.

Then there were bases. I had welcomed the destroyer bases deal, not for the sake of the destroyers, useful as these were, but because it was to the advantage of both countries that the United States should have the use of such bases in British territory as she might find necessary to her own defence; for a strong United States was a vital interest of the British Commonwealth, and vice versa. I looked forward therefore to an extension of the common use of bases for the common defence of common interests. In the Pacific there were countless islands possessed by enemy Powers. There were also British islands and harbours. If I had anything to do with the direction of public affairs after the war, I should certainly advocate that the United States had the use of those that they might require for bases.

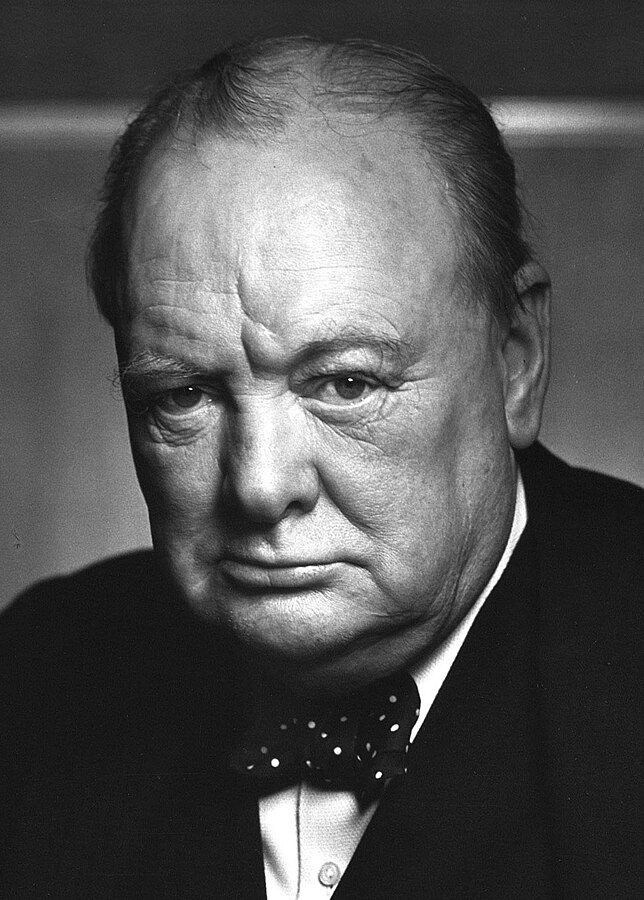

Churchill, Winston S.. The Hinge of Fate (Winston S. Churchill The Second World War) (p. 849). RosettaBooks. Kindle Edition.

Is anybody in the Trump administration thinking about these issues today?